This story is taken from Issue 18 of Highsnobiety magazine. You can buy the new issue here.

Words: Arthur Bray

Photography: Nicholas Yuthanan Chalmeau

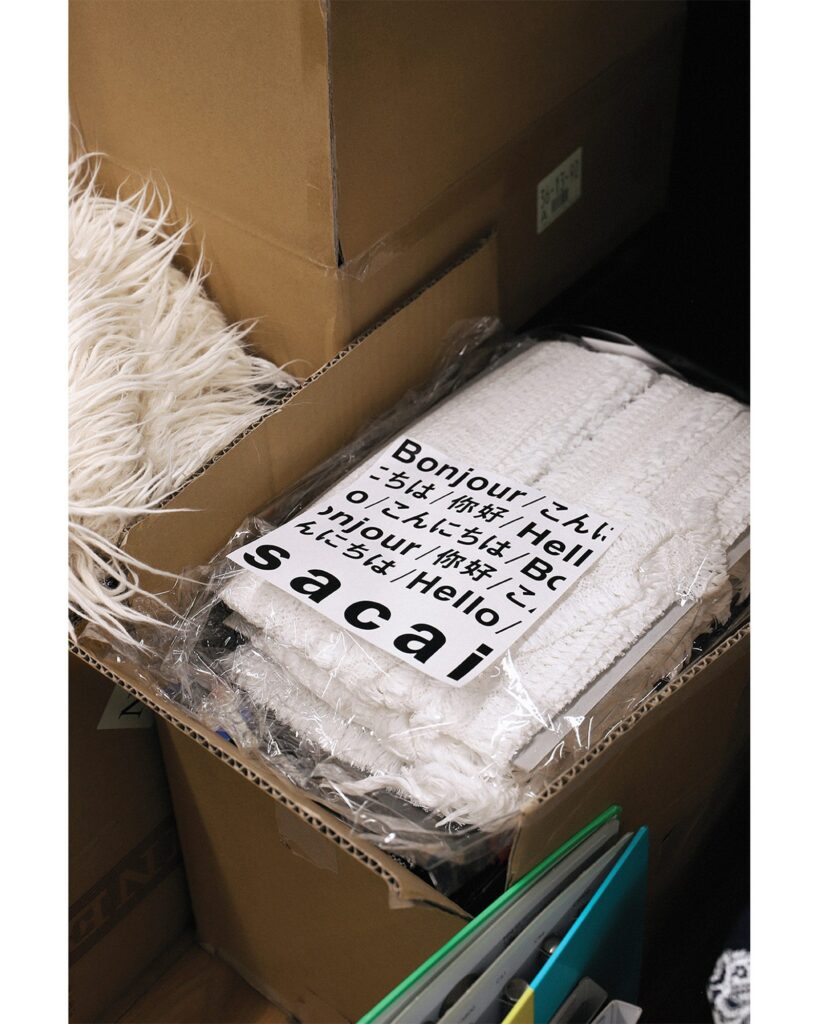

No designer creates quite like Chitose Abe. Her label sacai explores the multiple ways in which two garments can be arranged and hybridized, mixing casual sportswear with elevated tailoring. Her past as a pattern cutter at COMME des GARÇONS and as part of Junya Watanabe’s design team has given her the confidence and business acumen to remain independent — and even after 20 years, Abe and sacai continue to surprise with every collection.

As models walk the runway at the rehearsal for sacai’s Spring/Summer 2019 show in Paris, the thumping beat of Detroit techno legend Moodymann’s “I Can’t Kick This Feeling When It Hits” mixes with the jazz rhythms of Japanese composer Jun Miyake’s “Lillies of the Valley.” Two anthems from contradictory genres are brought together harmoniously, not unlike what sacai founder Chitose Abe does with her clothing. Challenging preconceived notions of fashion, denim jackets feature zigzag Apache prints and sleeves are replaced with varsity silk. Frayed shorts are paired with matching leggings. Elsewhere, loose-fitting button-down shirts with exaggerated collars are tucked into oversized plaid pants.

The familiarity of the prints and patterns is offset by a pronounced desire to stand out, to be different. It’s the middle of a sweltering Parisian summer and attendees are being treated to a session of masterful hybrid madness in the former garage that once housed the Jean-Paul Sartre-founded leftist newspaper Libération. Today, the space has become the world of sacai, an environment where adventure and imagination go hand in hand.

“Just because it’s a jacket doesn’t mean it cannot be something else,” Abe says backstage. Known for her innovative sportswear and delicate draping over timeless cut-and-sew tailoring, Abe regularly exhausts writers and editors’ supply of comparatives and superlatives with her ingenious, boundary-pushing designs. She has grown her three imprints — sacai, sacai luck, and sacai man — in an elegant yet defiant way. In Paris, as chaos rages backstage, she stresses, “There’s no hurry.”

The powerful calmness of her speech affirms her total control, whether leading the design team or even doing the accounting at the end of the month. “Sometimes I even go out partying all night,” she says cheerfully. sacai reflects Chitose’s transient and all-encompassing qualities. Her clothes are designed to be worn from day to night and made with the versatility of modern women in mind.

The 53-year-old cut her teeth at COMME des GARÇONS for eight years. She was a pattern maker under Rei Kawakubo before joining the design team of the COMME des GARÇONS subsidiary headed by Junya Watanabe. In both positions, she learned the importance of and gratification that comes with designing clothes unlike anything that has come before. At Junya Watanabe, she also met her husband, Junichi Abe.

After the birth of their daughter Toko, Chitose stepped out from under the COMME des GARÇONS umbrella. Junichi had already started the label ppCM with some friends in 1994, and for a short while, had enjoyed the freedom of not being bound to the fashion calendar. In 2004, after ppCM had disbanded, Junichi launched kolor, a brand often mentioned in the same breath as sacai, although the two labels are yet to collaborate. As a stay-at-home mother, Chitose was lacking a creative outlet, so Junichi convinced her to start her own brand in 1999.

sacai, named after Chitose’s maiden name Sakai, offered only a handful of pieces upon its debut. Abe started out with knitwear in response to a lack of exciting designs elsewhere at the time. In the first decade of its existence, sacai was regarded as a secret among Tokyo’s fashion elite. With a cosign from COMME des GARÇONS, rumors flooded the Japanese capital of a new brand that was a one-woman show.

Abe rejected tradition and didn’t rush to Paris or pursue common womenswear offshoots such as a fragrance line. The relative lack of urgency added to the designer’s mystique. Yet behind the scenes was a woman juggling work and parenthood, dedicated to doing things her own way, at her own pace.

sacai’s slow growth has paid off. The label’s first employee, Chico Hashimoto, is still in situ and ranks alongside creative director Daisuke Gemma, a former buyer, brand director, and shop owner who now works as Abe’s right-hand man. They work closely on set designs, soundtracking, and the brand’s coveted lifestyle collaborations with companies such as Nike, Levi’s, and The North Face. In 2003, the brand’s steady rise finally prompted Abe to rent a proper office. Until that point, sacai was housed in Abe’s apartment.

The designer admits her knitwear was interesting but lacked character. In the mid ’00s, she started experimenting with shape and form, toying with textile innovations on oversized silhouettes — now a signature of the brand. Abe’s desire to challenge norms is reflected in her meticulous approach to textiles. “I don’t buy fabric, I have them exclusively made for me,” she says.

This craving for the unique caught the attention of buyers in European and US stores. Barneys of New York and colette of Paris made pilgrimages to set up accounts, and so, in 2009, it felt only right for Abe to launch sacai in Paris. The label had two years of showroom presentations before scaling up to runway shows. As Abe notes, “Once you start doing runway, you can’t go back, as people expect it every season, so it’s important to know when you’re ready to make the jump.”

In 2009, she also offered a full men’s collection, a natural progression when so much of her womenswear pieces stem from menswear. Her first experimentation in the category was in 2006, when she launched sacai gem, a men’s line made exclusively for 10 Corso Como’s Aoyama store. COMME des GARÇONS followed, requesting sacai gem for Dover Street Market, where the diffusion line can still be shopped today.

Not putting all her eggs in one basket gave Abe room to experiment. It’s an approach that has metamorphosed into sacai’s business model. “It’s important to nurture ideas and let things run their course,” she says.

Outside of the main collections, Abe’s collaborations tell a similar story of evolution. sacai’s The North Face linkup has become covetable in a way not unlike the outdoor brand’s Supreme collaboration, with both going for upward of four times their original price on sites such as Grailed. The North Face exposed sacai to a wider audience and showed Abe’s deftness in turning the everyday into a wearable work of art.

Her “cut and paste” style of deconstructing and reconstructing pieces using different textiles is reminiscent of Junya Watanabe’s collaborations with The North Face, in which outerwear garments offered both internal and external functions with multiple styling options. Most of all, both Japanese labels’ collaborations highlight the ingenuity coming from the school of Rei Kawakubo.

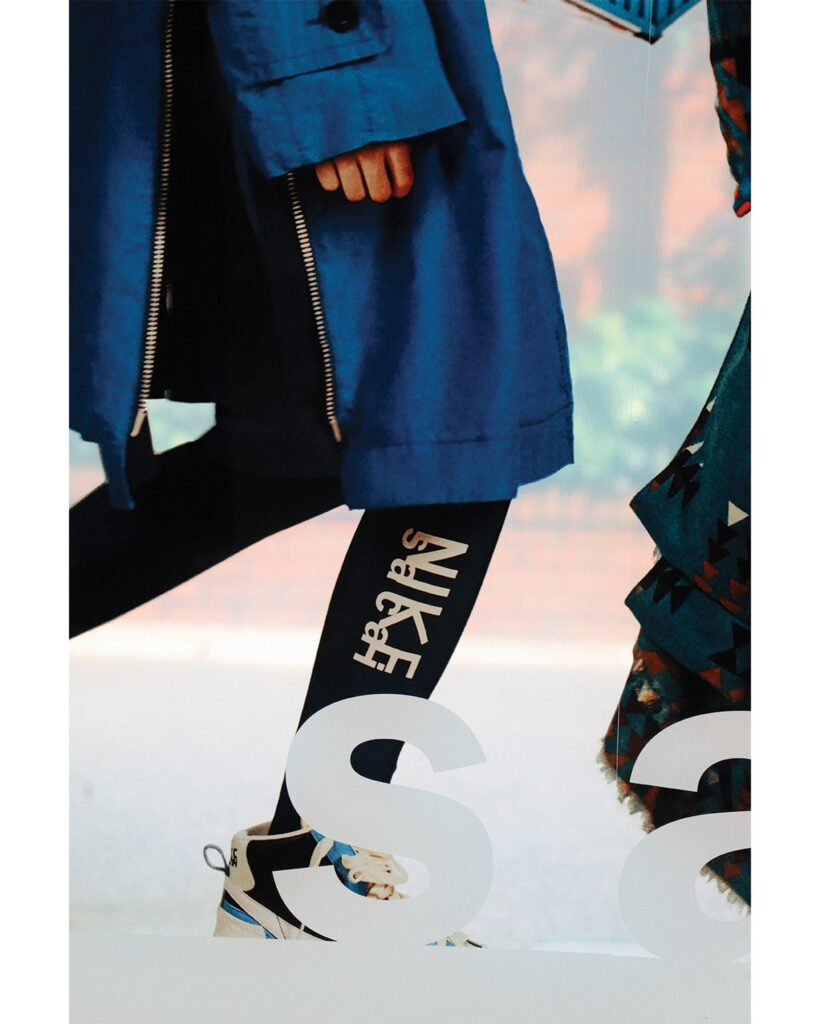

Abe showed her versatility with sacai’s first Nike collaboration in 2015, working with more technical materials. The collection added pleats and capes to athleisure silhouettes and brought predominantly style-conscious women to Nike’s conceptual NikeLab stores. More recently in Paris, jaws were collectively dropped by sacai’s double-Swooshed, double-tongued, double-laced hybrid Nike sneakers.

And Nike isn’t the only footwear brand to undergo the sacai treatment. Vans, Birkenstock, Hender Scheme, and UGG have all had models reinterpreted by the label. Abe’s penchant for collaborations stretches beyond brands to publications and artists, too. For Fall/Winter 2018, she collaborated with The New York Times as part of the publication’s “Truth” campaign in the era of “fake news.” And for Spring/Summer 2019, Abe has linked up with legendary LA tattoo artist Dr. Woo on a capsule collection.

Since its founding, sacai has grown into a label with an estimated $25 million in annual revenue and more than 90 stockists. Nonetheless, Abe approaches each project with the same inquisitive outlook. She still owns the label, and her creative freedom remains as important as ever. “I’ve stopped worrying about what will sell and just go with what I enjoy making, what’s authentic,” she says.

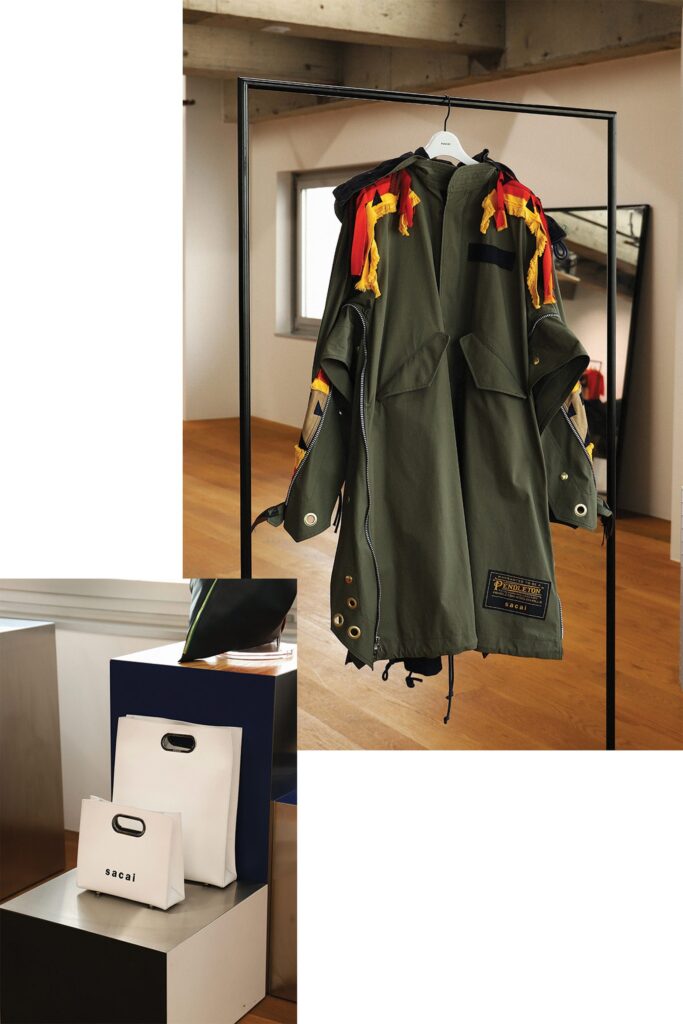

That’s a sentiment reflected in her recent collection in collaboration with Oregon label Pendleton, inspired by everything from reggae culture to Native American prints. It celebrates different ideals of freedom with sacai’s signature sense of playfulness. As Abe tells us when we sit down to talk, “If it isn’t fun, I don’t tend to do it.”

When did you know you wanted to work in fashion?

I saw Issey Miyake starring in a whisky commercial on TV when I was a kid and was immediately hooked to the idea of working in fashion. Before that, I didn’t even know you could make a living in fashion.

Where are you based?

I live in Tokyo and we work and design out of our atelier in the heart of the city, but I travel to Paris frequently. I think being based in two cities is quite usual now for many designers.

Your designs are crafted to reflect your own transient lifestyle. As a modern woman, how do you approach design?

If you asked me this before, I would have said I wanted my brand to be bigger, but now I’m interested in being real and authentic. There are many hows, and quality is always key, but how do you make an impact? This is something I constantly think about.

Would you say you always put yourself in the shoes of the wearer?

Yes, for sure. I don’t do market research and design with a specific audience in mind. Some designers target Europe or Asia with each release. I make clothes that I want to wear, that fit my lifestyle. No matter how conceptual the clothing might be, it always goes back to “Would I wear this?” If the answer is no, then I won’t go forward with the design.

I live in the city and travel between Paris and Tokyo. As a result, sacai’s clothing must be realistic as well as forward-thinking. There needs to be an element of surprise without being unapproachable.

sacai is known for reworking common fabrics and patterns such as plaid, pinstripe, and checkerboard print in innovative ways. How did you develop this style?

I’ve always been drawn to loud graphics since my time as a pattern cutter at COMME des GARÇONS. Wearability is key, but being unique is also important. With this in mind, I often create a synergy where recognizable patterns form one-of-a-kind silhouettes.

You started showing sacai in Paris in 2009. Was it always the plan to show your label in Paris?

Designers are defined by their shows and Paris is historical a place for designers to exude their ambition. I was at COMME des GARÇONS for many years. Coming from this world meant that it felt natural to orient the brand towards the direction we’re at now. I never really thought of showing anywhere else. From a business perspective, all the best stores come to Paris whether they’re from North America, Europe, or the Middle East.

Do you think there’s any similarity in your approach with sacai to Rei Kawakubo’s with COMME des GARÇONS?

I have my own design approach, but the main takeaway from my years at COMME des GARÇONS is autonomy. Also to create something exciting each season.

There’s no [better] privilege you can have today than owning your business fully. No one else to answer to except to yourself. Because I’ve remained true to my own views, business has also been very good. There’s something to say for authenticity. There’s no right or wrong way to the business of fashion, but I would say COMME des GARÇONS taught me the work ethic that is grounded in sacai.

What’s the biggest lesson you learned from the school of COMME des GARÇONS?

I learned how to balance business and creativity.

How do you ensure your designs are unique?

Functionality is key. I like to have fun with ideas, so naturally, pieces can have an artistic edge, but at the end of the day, they’re not art pieces. They may look like art pieces in a fashion show, but they have to be wearable. This synergy creates something new.

You’ve been lauded for using fabrics and textiles in interesting ways. Can you share your creative process?

Even before I know what clothes I’m going to make, I begin each collection with fabric selection and development. I start with very abstract concepts. This could be wanting an outfit to look stiff from a distance when it’s actually very soft. From there, I choose fabrics based on intuition and approach textile manufacturers to fit with exactly what I want.

Each season, sacai’s collections touch on various social and political issues. What motivates this?

The brand’s message is just an extension of me and my team. For example, we collaborated with The New York Times to amplify their “Truth” campaign, which was a reaction to Trump’s attack on the free press. Like The New York Times, we believe that high-quality, independent journalism requires resources, commitment, and expertise. It was a great chance to affirm this notion of what the publication declared perfectly. Saks Fifth Avenue in New York is also an iconic department store, and they helped share our capsule with an identity that we share.

How does being a Japanese brand affect the way you work?

Yes, sacai is a Japanese brand, but the design references aren’t confined by its heritage. Incorporating Japanese elements is not a necessity. However, our work ethic is very Japanese. We make our products in a very disciplined way.

How do you approach the men’s line versus the women’s line?

The thing about the women’s line is that I actually get to try it on myself, so it feels very personal. Whether it’s men’s or women’s, hybridization is always at the core. For the men’s, it took a few seasons to launch. When things finally picked up in 2015, it took some time to adjust, but now we’re in some good stores.

At your SS19 menswear show in Paris, there was a heavy use of Navajo print. What inspired the use of these patterns?

We collaborated with Pendleton on the prints on parkas and varsity jackets, which went through the sacai custom treatment. These were modernized and designed to fit with the theme of “free form,” which echos an outdoor, bohemian spirit.

How do you approach collaborations?

It’s important to have fun. If it isn’t fun, I don’t tend to do it. We’re an independent brand, so we can do whatever we want. This gives us the flexibility to work with sportswear brands or boutique labels. Having autonomy is important. Sometimes the best collaborations don’t have a commercial goal but exist to create something new. Daisuke [Gemma] and I often make the decision together.

How did your SS19 collaboration with Dr. Woo happen?

The key is to keep things real and intimate. We developed a close working relationship and cut out management and middlemen so we could create something authentic. I’ve been an admirer of his tattoo designs and Woo’s been looking to express his art on a different canvas, so this was a perfect collaboration.

And what is the ongoing thread that connects all of sacai’s work?

Hybridity.